A president and a justice: The shaping of securities law at the Supreme Court

Share

So many books cover the work of the Supreme Court that the Journal of Supreme Court History can review several of them in each issue. The overwhelming majority of those books, though, analyze the work of the court interpreting the Constitution. The court’s other task — interpreting federal statutes — remains markedly underrepresented. Of course, it can be hard to craft a sustained narrative about those cases when many deal with relatively obscure statutes that the court rarely examines – such as the Quiet Title Act, the subject of this year’s less than momentous decision in Wilkins v. United States.

While constitutional challenges tend to make bigger news at the Supreme Court, Congress’s most important products present themselves at the court each year. In that vein, I’ve written about the Bankruptcy Code, which has appeared in the Supreme Court almost every year since its adoption almost half a century ago. Similarly, securities laws have produced a steady diet of cases at the court each year since the adoption of the major securities statutes in 1933 and 1934. Two of the nation’s leading securities scholars, A.C. Pritchard (at the University of Michigan) and Robert Thompson (at Georgetown University), have produced a compelling and accomplished examination of that history in A History of Securities Law in the Supreme Court.

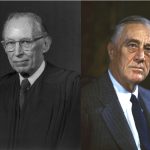

Pritchard and Thompson’s book is a fascinating read. The focus on a line of statutory analysis enduring decades produces a texture that at first seems much like David Currie’s book on the Supreme Court’s work in its first century. But this book has much more to offer the student of the modern court. Most notably, Pritchard and Thompson examine how a president and a justice, here President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Justice Lewis Powell, might wield influence over a particular area of law at the court. Their research into the justices’ files reveals not only how American securities law came to be, but also the complicated, and sometimes personal, inner workings of the court itself.

On the first point, scholars have debated for decades the role that Roosevelt’s threatened court-packing plan did, or did not, play in the court’s turn toward constitutional doctrines that were more tolerant of his New Deal program. Pritchard and Thompson document a much less well-known phenomenon: the effect on the court’s adjudications of the justices whom Roosevelt actually appointed. As they show, Roosevelt’s “strategic skill as judge picker” resulted in a group of appointees – larger than any other president since George Washington – who uniformly “accepted Roosevelt’s new role for government in the nation’s economy.” In the context of securities law, that led to a remarkably deferential court that gave the newly created Securities and Exchange Commission “an unfettered hand” for more than three decades.

The numbers are startling. From the adoption of the first major securities statute in 1933 until 1972, the Supreme Court adopted a restrictive reading of the securities laws in only 10% (3/30) of the cases involving the SEC. In assessing that number, remember that the Supreme Court’s control over its docket means that it has no reason to take easy or obvious cases. It usually is taking the cases in which reasonable minds (or at least lower-court judges) can differ about the result. For 90% of those cases to reflect an expansive conception of the statutory framework is a testament to an enduring perspective on the bench. So many presidents are famous for the failure of their judicial picks to follow the views of the one who appointed them. In this case, it seems, the litmus test that Pritchard and Thompson describe as driving Roosevelt’s selections was remarkably reliable.

My favorite thread in the book is its discussion of the effect of Justice Lewis Powell on the Supreme Court’s approach to securities law. To be sure, I should acknowledge that I clerked for Powell, and indeed the book in several places describes unpublished materials from the files of cases on which I worked. But what Pritchard and Thompson show is how remarkably successful Powell was at turning the tide of the court’s approach to securities law.

Other justices who preceded Powell on the court could claim an expertise in securities law. Justice Felix Frankfurter, for one, had played a key role in the enactment of the securities laws, and Justice William Douglas, for another, had been chairman of the SEC. However, as Pritchard and Thompson show, neither Frankfurter nor Douglas played a major role in the court’s securities cases. Pritchard and Thompson argue cogently that Frankfurter’s abrasive personality undermined his ability to narrow the capacious power the justices afforded the SEC, and that Douglas’s influence was limited by his broad approach to recusal, which left him participating in few of the court’s securities cases for the first 15 years he was on the bench.

It was Powell, whose experience as a securities lawyer was entirely in private practice, who turned the court’s approach to securities law almost on a dime. The court that for decades had been reliably generous to the SEC showed a much different face, at least for the 15 years, from 1972-1987, that Powell sat. During that period, by Pritchard and Thompson’s count, the court took a restrictive approach to the securities laws in most of its cases, a sharp turn from the overwhelmingly deferential approach during the first 40 years of those laws. And Powell led the way in those restrictive decisions, as he dissented in only one of the 41 securities cases in which he participated, consistently adopting “the most pro-business position of any justice.” As Pritchard and Thompson observe, his polar position in those cases was a far cry from the nuanced “multi-factor balancing tests” that left him in the “middle ground [in his] more widely noticed constitutional law opinions.”

Powell’s influence was not limited to the decisions the court reached, as he also had a crucial role in the selection of cases. The court’s securities law docket ballooned during Powell’s tenure – from approximately 1.5 cases per year before he took the bench to three cases per year during his tenure, compared with just over one case per year since his retirement. Combing through the justices’ files, Pritchard and Thompson reveal Powell’s success in his hard work, organization, unchallenged expertise (as the only securities lawyer appointed to the Supreme Court), and unceasing efforts at collegiality, a marked contrast to their portrayal of Frankfurter.

The book is a joy to read for anybody interested in understanding the day-to-day work of the Supreme Court, and especially for its look at the way that the personalities of the justices shape the court’s output. To see how the justices are working when not so many people are following every word they say, this book is an excellent choice.

The post A president and a justice: The shaping of securities law at the Supreme Court appeared first on SCOTUSblog.