The statistics of relists over the past five terms: The more things change, the more they stay the same

Share

Regular readers of SCOTUSblog know that in addition to flyspecking the Supreme Court’s docket most weeks to identify cert petitions that the justices are considering repeatedly at consecutive conferences (a practice called “relisting” cases), we periodically crunch the numbers to determine what relisting portends about what the court is likely to do with those cases it has relisted. Relists are a hint that at least some justices want to take a closer look at a case, which is often an indication they may want to grant review or perhaps take summary action in the case. Relists are the shadow docket’s workaday cousin and generally too dull to get a Senate hearing.

A lot has happened since the last time we ran the numbers on the Supreme Court’s relist docket, which was for the 2017-18 term. Because of pandemic-related shortages, it’s harder to buy bikes, tennis balls, and canned goods. The children … they are always home. Oh, and somewhere along the way the Supreme Court got another new justice and discovered that livestreaming oral arguments would not bring about the end–times. But in any event, now we’ve calculated the statistics for the 2018, 2019, and 2020 Supreme Court terms, and we’ve compared them to our earlier observations for the 2016 and 2017 terms. Based on our five-year retrospective, we are happy to report that one thing has stayed mostly the same: Relists remain one of the best predictors of whether the Supreme Court will grant certiorari.

Relists and cert grants: Together forever

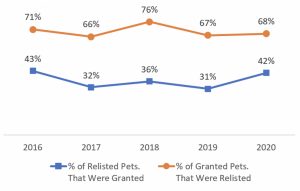

While the justices grant only the tiniest percentage of petitions – about 1% of all petitions and about 4% of petitions filed by paying petitioners – relisted cases fare far, far better. For the court’s 2016 to 2020 terms, between 31% and 43% of petitions that were relisted at least once were eventually granted review. And between 66% and 75% of all cases granted certiorari were relisted at least once. The odds vary a bit from year to year, and grants among relists are recently on an upswing, but the basic truth remains: The justices mostly grant cases that they have relisted, and relisted cases are far more likely to be granted.

While the justices grant only the tiniest percentage of petitions – about 1% of all petitions and about 4% of petitions filed by paying petitioners – relisted cases fare far, far better. For the court’s 2016 to 2020 terms, between 31% and 43% of petitions that were relisted at least once were eventually granted review. And between 66% and 75% of all cases granted certiorari were relisted at least once. The odds vary a bit from year to year, and grants among relists are recently on an upswing, but the basic truth remains: The justices mostly grant cases that they have relisted, and relisted cases are far more likely to be granted.

Less is more with relists

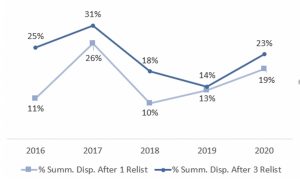

Another longstanding reality is that two relists are not better than one, but are still far better than no relist at all. In other words, the odds of a grant are at their highest when a case is first relisted; as the case is relisted additional times, the odds of a grant fall as it becomes more likely that the court intends to enter a summary decision (the practice by which the court summarily grants cert and issues an opinion, typically reversing or vacating the judgment of the lower court, without receiving merits briefing or hearing oral argument). Between 2016 and 2020, a case relisted two or more times saw its odds of a grant fall to as low as 11 to 15% – still better than the odds of a non-relisted case being granted, but significantly lower than for first-time relists. It appears that the justices generally don’t need that long to decide whether to grant a case and to investigate potential vehicle problems. If the case sticks around longer, it’s because something else is going on.

Another longstanding reality is that two relists are not better than one, but are still far better than no relist at all. In other words, the odds of a grant are at their highest when a case is first relisted; as the case is relisted additional times, the odds of a grant fall as it becomes more likely that the court intends to enter a summary decision (the practice by which the court summarily grants cert and issues an opinion, typically reversing or vacating the judgment of the lower court, without receiving merits briefing or hearing oral argument). Between 2016 and 2020, a case relisted two or more times saw its odds of a grant fall to as low as 11 to 15% – still better than the odds of a non-relisted case being granted, but significantly lower than for first-time relists. It appears that the justices generally don’t need that long to decide whether to grant a case and to investigate potential vehicle problems. If the case sticks around longer, it’s because something else is going on.

More relists, more likely to be summarily resolved

That brings us to our next point: As the number of relists increases, so does the chance that a relisted case will eventually be resolved through a summary disposition. This is consistent with our findings in past years. While it remains true as a general matter that serial relists are more likely to result in a summary disposition, the numbers are generally down from a high during the 2017 term.

That brings us to our next point: As the number of relists increases, so does the chance that a relisted case will eventually be resolved through a summary disposition. This is consistent with our findings in past years. While it remains true as a general matter that serial relists are more likely to result in a summary disposition, the numbers are generally down from a high during the 2017 term.

One-and-done predominates relists

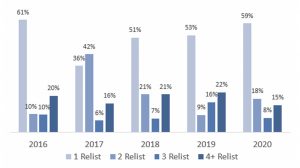

A significant change in relist practice is that the court has tended to relist fewer cases, and the cases that are relisted tend to be relisted fewer times. In the 2017 term, two-thirds of relisted cases were relisted two or more times, whereas in the 2018 to 2020 terms, between 51% and 59% of relisted cases were “one and done” – relisted just once before disposition.

A significant change in relist practice is that the court has tended to relist fewer cases, and the cases that are relisted tend to be relisted fewer times. In the 2017 term, two-thirds of relisted cases were relisted two or more times, whereas in the 2018 to 2020 terms, between 51% and 59% of relisted cases were “one and done” – relisted just once before disposition.

Relist numbers falling

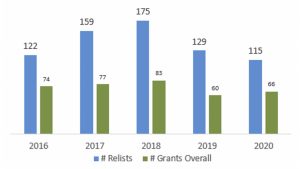

The falling number of relisted cases may reflect the shrinking number of granted cases in recent terms – down to 60 in 2019 and 66 in 2020 from around 80 in 2017 and 2018. The justices may think there’s no point taking a second look at a case by relisting it if they’re unlikely to grant review in any event. The cause of the court’s shrinking docket could be the subject of its own article. But our five-year restrospective confirms that relists remain one of the best means of gaining insight into which cases most interest the justices – and which cases are likely to make up the merits docket even as it shrinks.

The falling number of relisted cases may reflect the shrinking number of granted cases in recent terms – down to 60 in 2019 and 66 in 2020 from around 80 in 2017 and 2018. The justices may think there’s no point taking a second look at a case by relisting it if they’re unlikely to grant review in any event. The cause of the court’s shrinking docket could be the subject of its own article. But our five-year restrospective confirms that relists remain one of the best means of gaining insight into which cases most interest the justices – and which cases are likely to make up the merits docket even as it shrinks.

October Terms 2018 through 2020 relist flowchart

The authors thank Casey Howard for toiling through three years of Relist Watch articles to gather the raw data – let’s never get three years behind again.

The authors thank Casey Howard for toiling through three years of Relist Watch articles to gather the raw data – let’s never get three years behind again.

The post The statistics of relists over the past five terms: The more things change, the more they stay the same appeared first on SCOTUSblog.

[…] review (certiorari or “cert”) to a case after just one Friday conference. Petitions may be “re-listed,” that is, deferred for additional consideration at the next […]