Surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis guidelines: dogs and cats

Antimicrobials are often used at the time of surgery and it’s widely accepted that there is tremendous overuse in human and veterinary medicine. Antimicrobial prophylaxis indicated in some surgical patients to reduce the risk of surgical site infection, but a large percentage of use is unnecessary and is based on habit or fear (and antibiotics are often used to make the surgeon or owner feel better).

Clinical guidelines are an advancement in care, and the field of guideline development has progressed significantly in recent years. We’ve moved from primarily expert-opinion based narrative guidelines to evidence-based, structured guideline development, which should yield stronger, less biased and more defendable guidance. It’s never perfect since there are lots of evidence gaps. Also, guidelines are meant to cover the majority of situations, not every possible case, so there are always exceptions to the rule. However, good guidelines can support good clinical decisions.

New surgical prophylaxis guidelines for dogs and cats have recently been released. The guidelines, coordinated by our ENOVAT (European Network Optimization of Veterinary Antimicrobial Therapy) subgroup, are the culmination of a few years of work, and are underpinned by a scoping review and systematic review (coming soon).

The guidelines have a heavy emphasis on ‘don’t use them in this situation’ since that’s what the evidence supports, but also highlight situations where antimicrobials are recommended and provide details about optimal approaches.

A couple terminology aspects to start. We used a GRADE-based approach. That culminates in a strong or conditional recommendation for or against an intervention (or a situation where we can’t recommend one over the other).

Strong recommendation: “We recommend…”

- Strong recommendations for an intervention (here, antibiotic prophylaxis) are made based on moderate to high certainty evidence of the effect of the intervention, plus supporting value amongst various other domains (importance of the problem, benefits, harms, cost:benefit, equity, acceptability….).

- Strong recommendations against can be made based on similarly moderate-high certainty evidence of where there is lower certainty evidence about the effect but moderate/high certainty evidence about potential harms. The default is not to use the intervention so a strong recommendation against can be made without solid data showing it doesn’t work.

Conditional recommendation: “We suggest…”

- Conditional recommendations are made when the recommendation is based on low certainty evidence or when there is a lot of uncertainty or variability about acceptability, applicability, equity or other factors that mean it might not be an ideal or preferred approach for most. (For example, we’re not going to make a strong recommendation for a treatment that’s so expensive only a small subset of the population could do it).

- A conditional recommendation doesn’t mean that the treatment is less effective than one with a strong recommendation. It means the confidence and certainty behind the recommendation is less, and/or that it’s value is more situational, being a preferred choice in some situations but not others.

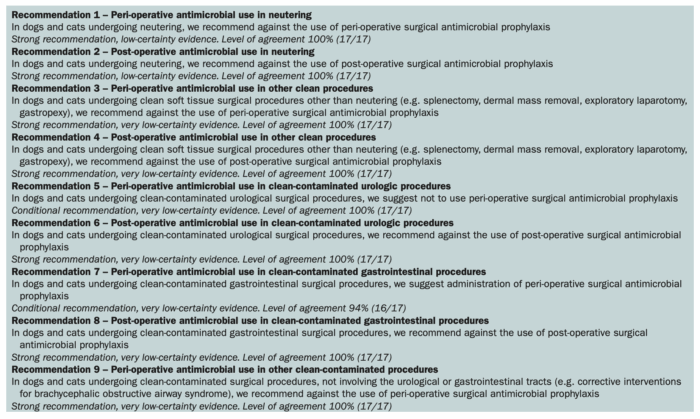

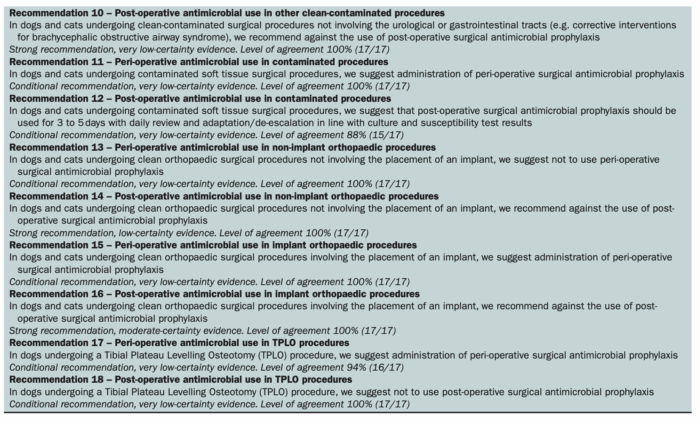

Here’s a synopsis. Check out the full text for more details and explanations.